I recently had a conversation with my colleague, Donna Henderson, Psy.D., about a form of dyslexia that she has noticed in some of her clients with autism. My curiosity was piqued because I had noted similar patterns of spelling errors in a number of my clients, but couldn’t find a description of the phenomenon in books and articles describing more common forms of developmental dyslexia. When I asked Dr. Henderson for details, she sent the following essay, which she has graciously agreed to allow me to post. – Sarah Wayland

by Donna Henderson, Psy. D.

Poor awareness of the sounds of language or a lack of understanding of the spelling-sound correspondence is the cause of the most common type of dyslexia. People with this type of dyslexia will make spelling errors that do not make phonetic sense (such as spelling “desk” as deks or “with” as weth). In contrast, I have noticed that some of the children I work with have an unusual pattern of spelling errors. These kids seem to understand which letters go with which sounds, but they actually over-rely on the letter-sound correlation. For example, they might spell the word “garbage” as garbij or the word “wiggle” as wigul.

To understand these different types of errors, it’s important to first understand how children learn to read as well as what typical dyslexia looks like. It all starts with the phoneme.

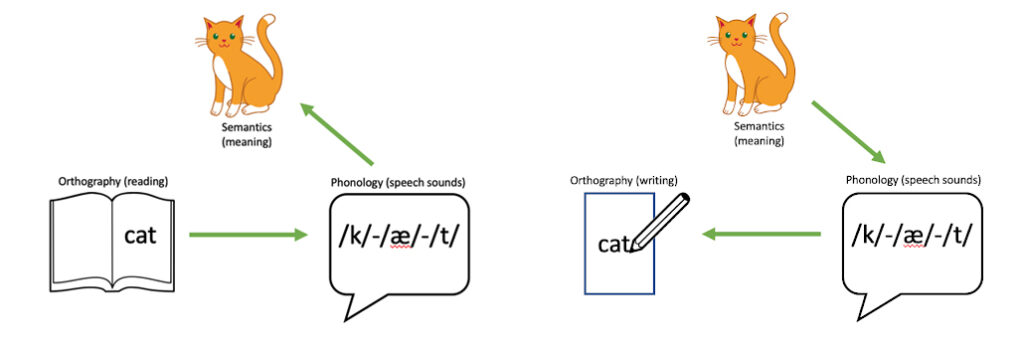

A phoneme is the smallest unit of sound, and there are 44 phonemes in the English language. In the word “cat”, for instance, there are three phonemes (/k/ – /æ/– /t/). Both speaking and reading rely on being able to identify, distinguish, blend, and manipulate these phonemes. Good readers know that specific written letters are associated with particular sounds (the phonemes) and that the sounds (and thus the letters) must be in the proper order.

However, the English writing system does not necessarily observe a one-to-one correspondence between letters and sounds. For example, if we see the letter “k” we associate it with the /k/ sound, but if we see the letter in a certain context (knife), we know that the sequence of letters will alter the sound of that particular “k”. Likewise, the letter “c” can be pronounced as /s/ or /k/ (as in “concise”), depending on the word’s origin and the letters that surround it. Knowing the rules that govern a letter’s pronunciation can make decoding words much easier. There are many of these irregular words, such as “laugh” and “neighbor.” These words cannot be sounded out; to read or spell them, the reader must either be able to recognize the word automatically from memory (a sight word) or know how to apply the unique reading and spelling rules.

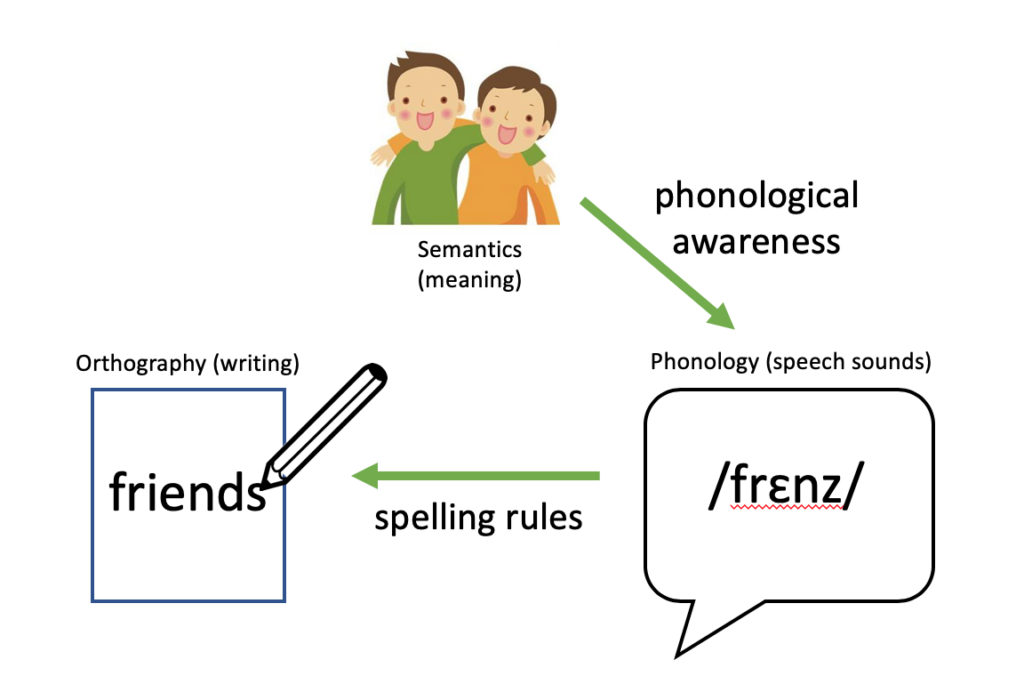

The phonological awareness skills (to sound out regular words) coupled with a knowledge of the spelling rules of English (to cope with irregular words) are both necessary for fluent reading and writing.

In the most common type of dyslexia, phonological dyslexia, people do not have adequate phonological skills, so they have difficulty sounding out or spelling even regular words.

Other students, however, may have adequate phonological skills but fail to fluently use the spelling rules of a language, particularly for irregular words. They may continue to erroneously believe that words are a perfect representation of spoken phonemes. This type of dyslexia is less common and is referred to as surface dyslexia or orthographic dyslexia.

Whereas people with phonological dyslexia have difficulty sounding out words, people with surface dyslexia rely on the spelling-sound correspondence too heavily. For them, words that cannot be sounded out (the irregular words, such as “through”) are misread or misspelled because people with surface dyslexia rely on sounds when spelling (seshen for “session”) without applying the spelling rules of their language and without being flexible for words that don’t follow the typical rules. This can lead to very slow and effortful reading as well as poor spelling.

Curiously, over time I became aware that the only children I tested who had surface dyslexia were autistic, and I also came to realize that quite a few of them had it. To be clear, it is entirely possible that there are non-autistic children with this type of dyslexia; I simply have not come across any of them.

I also consistently noticed that some of these same children use somewhat random capitalization and punctuation, much more than one would expect with just inattentive errors. Literally, these kids will randomly Capitalize, words and insert Punctuation At Various points in. sentences.

It was this observation that led me consider whether this form of dyslexia was actually a reflection of the context blindness described by Peter Vermeulen in his book, Autism as Context Blindness. We sound out and spell irregular words based on context (is it “dear”? or “deer”?), and we also use punctuation and capitalization based on context (where it appears in the sentence).

There is still much we do not understand about this presentation of dyslexia, particularly in students with autism. Moreover, the extent it is related to context blindness, rigid thinking, or other factors almost certainly varies from person to person. Understanding which factors contribute to the specific form of dyslexia observed in a child will help inform the best type of reading intervention for that child.

If you have a child who is struggling to read, you will want to work with a professional who has both broad and deep knowledge about reading skills, and who can formulate direct multi-sensory instruction based on the specific needs of the student. This might be a speech language therapist (CCC-SLP) who specializes in reading disabilities, a certified Educational Therapist (BCET or ET/P), a psychologist who specializes in reading (PhD), or a Certified Academic Language Therapist (CALT). Make sure to ask how they will work with a student who has your child’s profile to see if the approach they recommend makes sense.

Donna Henderson, Psy.D. is a neuropsychologist/detective with The Stixrud Group. She works with wonderful people, who are struggling in some area of their lives to figure out why, and to help them do better. She has loved doing neuropsychological evaluations for over 25 years.

Want to learn more about neurodivergent brains and how they work? Join my email community to receive articles on the latest research, articles, and learning opportunities about neurodiversity.

Share this post on Pinterest!

I just came across this interesting article ! My child is not on the spectrum and has this type of dyslexia. Really interesting x

We just received the same diagnosis for our son, who also is not on the spectrum. I didn’t know what orthographic dyslexia is so am doing some googling and came across this also. Very helpful read!

Thank you for this!

My daughter was identified as potentially dyslexic in kindergarten when her reversals and writing skills did not seem to be improving in the same way as her classmates. We kept an eye on things and at the beginning of third grade I started pushing for an IEP because she was clearly struggling. I started collecting every reading and writing assignment I could to show that she is NOT being lazy (as her teacher wanted to claim). When she was approved for services at the end of third grade, the stack of papers was literally a foot tall, sorted for reading tasks (all perfect or near perfect scores unless it was a read aloud fluency) and writing tasks (almost all failing scores). Her state testing scores and IEP eval forms had the same pattern. Your description of orthographic dyslexia is exactly my child and likely part of why it was a struggle to get the school to recognize it as dyslexia, since it seems like it is actually a more recently defined subtype (c 2014?). She is heading to eighth grade this year and transitioned from an IEP to a 504 last year, but she still spells largely phonetically unless she has spell check. Phonemes were never the issue, comprehension and vocabulary have always been well above grade level, but putting phonemes together to correctly build a word (reading aloud and writing) is almost impossible unless it is a high frequency word. Even that isn’t a guarantee!

Your observation of seeing it more frequently with spectrum disorders is interesting. My daughter does show several spectrum markers (sensory overload, spending time in her own world, difficulty processing change, etc.), but I’ve always ascribed it to the ADHD/anxiety combination. I’ll be doing more reading on it, for sure!

I feel like you’ve provided some missing pieces of information which will help me advocate for her and support her in eschool this year and as she prepares for high school. Thank you again!

My daughter went through Barton training program at early age, I wonder if this is why she is now being diagnosed surface dyslexic? She has been taught the rules in phonetics…

I’m so glad you found this article helpful! I used to work with adults who developed reading disabilities after brain trauma. For those people, this kind of dyslexia was fairly common. When I started working with children, I saw lots of discussion about “dyslexia” which nearly always referred to phonological dyslexia. There was hardly any discussion of orthographic dyslexia. At first that was really confusing – but Dr. Henderson helped clear it up for me!

I was diagnosed with dyslexia. I really struggle with school. I seem to have to take longer to study, especially reading. When I have be fast at taking notes I have a real problem with keeping up! I mix numbers and letters together. But when I understand something I get it!

Yes! I know many really smart people who have trouble with reading and writing. I really like the book The Dyslexic Advantage by Brock Eide & Fernette Eide. They explain how dyslexic people see the world in a very different way than non-dyslexic people – which means they can solve problems in unique ways that other people might not think of.

Yes I am the same, get something to stick in my brain and I’m exceptionally great at it…

Dr. Wayland,

Thank you so much for this article! My first grade son was FINALLY diagnosed by an incredibly attuned school psychologist after fighting since he entered preschool to get this recognized… she has labeled it as orthographic processing disorder – but let’s be honest schools won’t actually supply any acknowledgement beyond what they legally have to. As a teacher for almost twenty years I come to the IEP table armed both with enough knowledge to be dangerous to my son’s district and an attorney. To watch my son who has been diagnosed as 2E struggle to read when he can carry on conversations about preferred subjects better than some of my high school kids has been so hard to watch as a mom. Finally, we have some direction to begin looking for help beyond what the school is required to provide so that he can be his best and not become enraged that his younger brother is reading higher than he is. The struggles with obtaining my son the services he needs and is entitled to by law has led me back to school for an additional masters degree in SPED and a reading concentration – I truly believe knowledge is power. I am curious if you are aware of any specialists in the Chicago area that recognized and work with students who are ASD and orthographically dyslexic?

I’m so glad it was helpful! I don’t know resources in the Chicago area, but I’m sure you can find someone. A speech language therapist (CCC-SLP) who specializes in reading disabilities, a certified Educational Therapist (BCET or ET/P), a psychologist who specializes in reading (PhD), or a Certified Academic Language Therapist (CALT) should be able to help, but I’ve found that people specialize within those professions so you’ll want to specifically ask about their experience with orthographic dyslexia and autism. Here’s a link to a post I wrote to help parents find good providers for working with their kids.

Susan Barton is a great resource, the public school tested my daughter and said she didn’t qualify for a IEP although everyone on team was agreement she had a learning difference, I knew she was dyslexic as I am and my father. Had to put her under ADD umbrella for services, as she had a wrong diagnosis once but we used it… 3 years later IEP renewal came up in junior high, testing improved and psychologists said your daughter has surface dyslexia, (ah ya) I’m aware!!! The schools are leaving dyslexic children suffer! I paid for my daughter to learn phonetics with Barton and hence why she isn’t phonetically challenged. Good luck

Are you familiar with David Kilpatrick’s research on dyslexia? Phonological awareness (at an advanced level) and phonics knowledge are both necessary for orthographic mapping to take place. “Orthographic processing” is not a separate skill or function. I find it odd that people are diagnosing children with “subtypes” of dyslexia when no subtypes are recognized in the DSM-5, by the IDA or by any other groups or governing bodies.

I think this is a case where the official diagnosis is an umbrella term that covers a lot of specific (and distinct) challenges. When I worked with adult clients who had traumatic brain injury, acquired orthographic dyslexia was both diagnosed and treated as distinct from dyslexia that stems from difficulty with speech sounds (phonology). When I shifted to learning about developmental dyslexia, I was surprised that no one addressed this issue in kids. I think that’s because developmental dyslexia has a very different etiology (and profile) from acquired dyslexia.

This is also true, by the way, for “disorders of written expression” which can involve challenges at many levels, from skills like planning and organizing your thoughts right down to the fine motor skills necessary to coordinate your fingers while writing (and many steps in between).

Good reading language interventions (including those recommended by the IDA) involve assessment for *all* the skills involved in interpreting the written word. That’s what “structured literacy” is all about!

There is an interesting article by David Kilpatrick on the origins of the subtypes of dyslexia that speaks to the distinction between losing skills that one already has, as in traumatic brain injury, and the developmental trajectory seen in typical development:

http://www.myschoolpsychology.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/Dyslexia-Subtypes-Based-upon-the-Dual-Route-Model-of-Reading.pdf

Thanks for that article – it helps me understand. Dr. Kilpatrick is making an argument that there is no evidence for the dual route dyslexia subtyping model. While the specific model may not be correct, I think it’s important to note that in the field of cognitive psychology and developmental reading disabilities, there is significant disagreement on this point. The work of Mark Seidenberg (Language at the Speed of Sight) or Stanislas Dehaene (Reading in the Brain) readily acknowledge the contributions of both visual and auditory processing, the interactions between them, and the influence of top down/contextual processing during the act of reading. The point Dr. Henderson is trying to make (and which I absolutely agree with) is that there are children who over-regularize, and have trouble learning the exceptions to the generalized spelling rules.

Wow, all great points… my daughter is trained through Barton and now she is labeled surface dyslexic… hmmmm

I don’t believe children who suffer from othrographic dyslexia have to have Autism. I am 49 years old and suffer from this. My 11 year old also suffers from it. Yes it is hereditary. But no it is not just children that also have Autism!! It would be wonderful if teachers would be able to recognize this. My daughter has been suffering with this since 1st grade. I finally had a seasoned teacher recognize this in the 5th grade. My daughter was always on the honor roll. She was so smart she was able to hide it from the other teachers.I had been beating my head on walls until the Lord sent this wonderful 5th grade teacher in her life. Now hopefully on the way to getting her the correct help in the 6th grade!!

Thanks for posting Nicole! Your timing is excellent; I recently asked Peter Vermeulen whether non-autistic people could also have context blindness and he said replied “I see a very strong link between context blindness and stress. So, it is possible for all other conditions that involve stress, to see signs of context blindness.”

I also used to work with adults who had acquired dyslexia after a traumatic brain injury (usually stroke), and many of them had this form of dyslexia. It would make sense that there is also a congenital brain wiring difference that leads to it. I’m VERY glad your daughter is finally getting some help.

I think autism, especially in very bright girls, probably goes unnoticed and undiagnosed a lot. They are so brilliant at masking.

Thanks for posting this essay. You’ve made a great connection for me and my bright, autistic and surface dyslexic children!! Go neurodiversity!

Oh my, yes, Lucy! In fact, Dr. Henderson & I are currently writing a book on how to diagnose the more subtle presentation of autism. It’s due to be released in October of 2022. I’m currently working on the chapter on autistic strengths and agree: Go neurodiversity! We need all kinds of thinkers!

I have had my son evaluated for Autism, but was told that he makes eye contact and interacts well. He was 2 or 3 at the time. He was a difficult baby. On occasion would not respond to an adults silly antics to gain his attention and would melt down if I hurried him or heaven forbid I took a different route to daycare. He started speaking late and then had articulation issues….still has articulation issues. We are now in 2nd grade, and he appears to have dyslexia and an orthographic processing problem. We are in the midst of testing and will know more in the coming week.

Best of luck, Cheryl. Your son sounds like an amazing kid. I hope you get some answers that make sense and allow you to help him!

Thank you for this helpful article. I am a certified Barton tutor and dyslexia screener. I just recently received a call from a parent whose son was diagnosed with Orthographic dyslexia and she was inquiring about my tutoring services. After reading the article I’m still a little unclear. In your opinion, would an OG based system like the Barton reading and spelling system be a suitable means of helping these children with reading and spelling? Or do you feel they need a different method or approach?

I do think OG would be helpful. The parts you would want to focus on are how the context determines the meaning of the word, and therefore which spelling is appropriate. Helping the student to understand the different word roots, their origins, and thus their spellings will be super helpful.

I have two boys with dyslexia. It is suggested in an IEP one of them may have “surface dyslexia.” I have done a lot of reading (and getting trained) to gain knowledge on how to teach and support my kids. Would a program like Structured Word Inquiry (SWI) be meaningful to my child with surface dyslexia?

Elizabeth – I hadn’t heard of “Structured Word Inquiry” until your comment, so I looked it up. While I think it will be helpful for learning the spelling rules for individual words, your son with surface dyslexia will likely also need instruction on using the context in which words appear to determine how to correctly spell those words. If he also has trouble with capitalization and punctuation, he will definitely need instruction regarding sentence structure, and the rules around when to capitalize and which punctuation marks to use where.